Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation

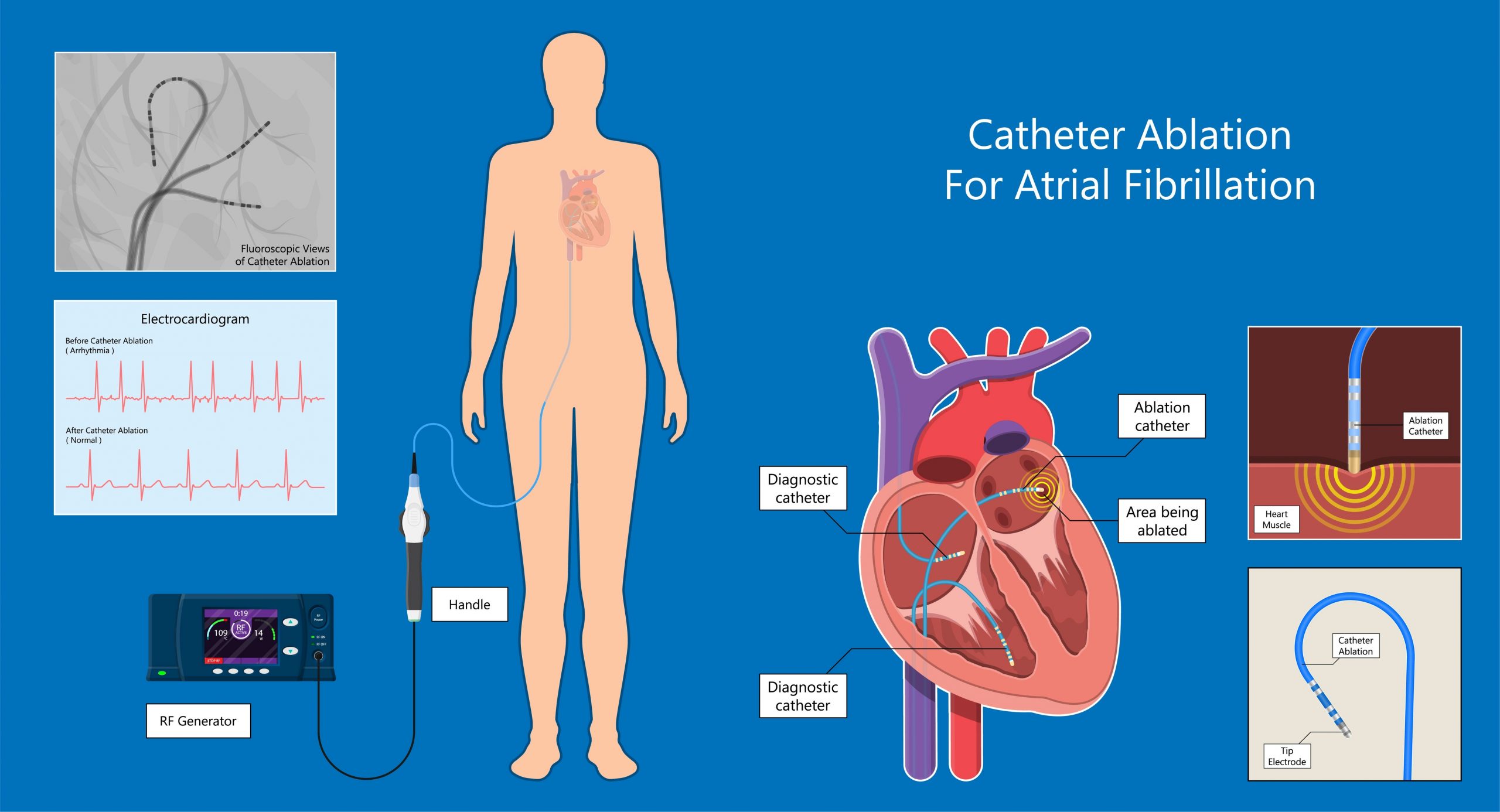

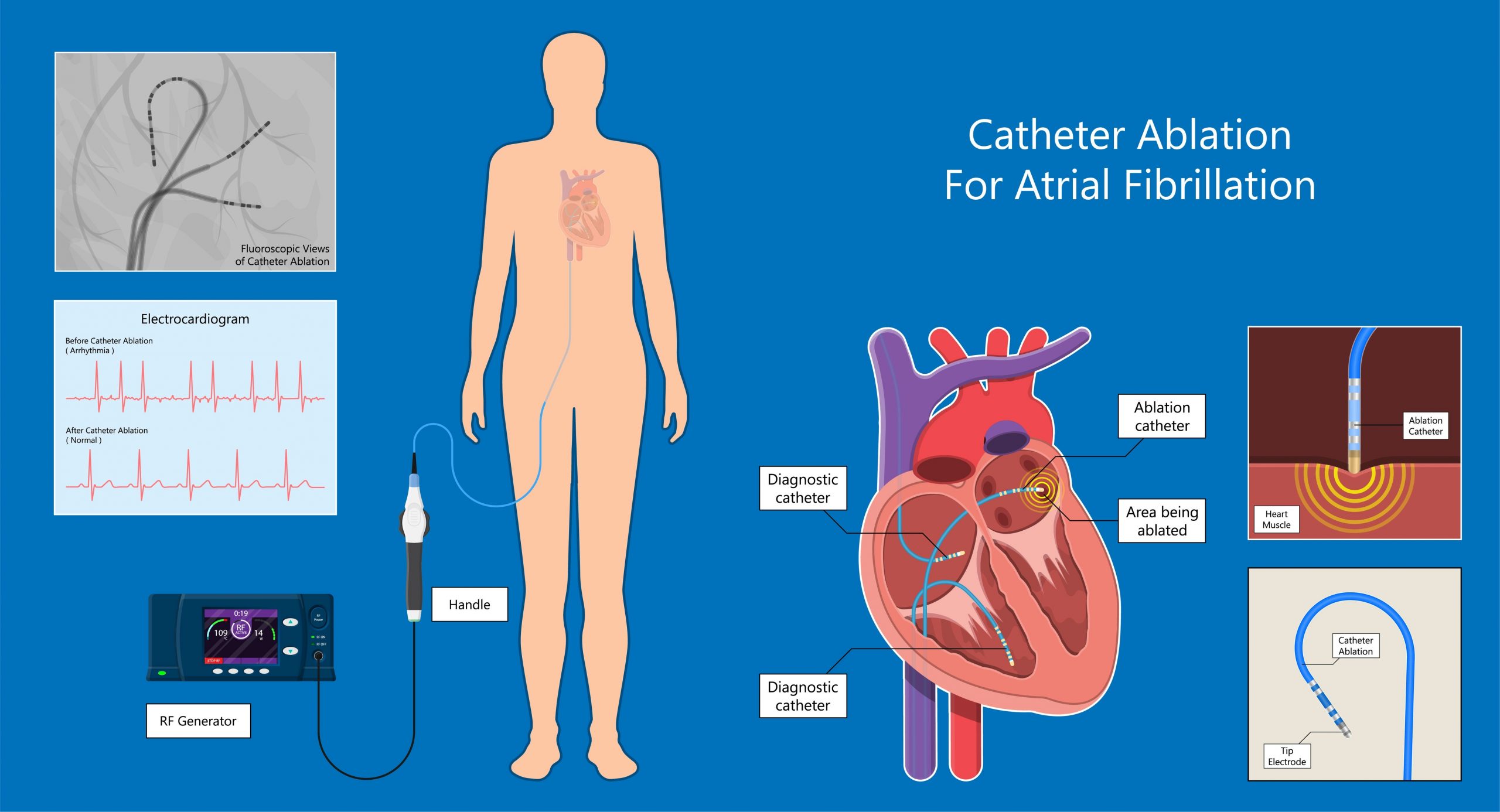

Catheter ablation is an atrial fibrillation treatment that is done by a specialized cardiologist, called an electrophysiologist (EP). Electrophysiologists focus on the heart’s electrical system and deal with afib and other irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias).

A catheter ablation is a minimally-invasive procedure that is generally less invasive than surgery. It is a commonly-used treatment for atrial fibrillation as well as other cardiac arrhythmias. Like other atrial fibrillation treatments, it is most successful in treating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, but much progress has been made in treating persistent and longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation as well.

It is done on a beating heart in a closed chest procedure. Small punctures are made in the groin, arm, or neck area, and thin, flexible tubes, called catheters, are inserted and threaded to the heart. Once there, the catheter’s tip is threaded through a tiny incision in the septal wall between the left and right atria. It is positioned to ablate tissue around the pulmonary veins or at other sources of erratic electrical signals that cause the irregular heartbeat.

The catheter uses an energy source, such as radiofrequency energy (radio waves), cryothermy (intense cold), laser energy (light waves), or ultrasound energy to create a lesion of scar tissue, called a conduction block, that stops the erratic electrical signals from traveling through the heart.

Evolution of Catheter Ablation

Catheter ablation originated in the 1980s for treating cardiac arrhythmias and started being used for atrial fibrillation ablation in the 1990s. Variations of the procedure have evolved over time.

Radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation is the traditional method of catheter ablation. Radiofrequency catheter ablation uses radiofrequency energy to create intense heat to ablate heart tissue. Radiofrequency catheter ablation is typically some variation of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI). You may hear it called pulmonary vein antrum isolation (PVAI) or pulmonary vein ablation (PVA). The goal of the procedure is to eliminate the irregular heartbeat that research has shown typically originates from the pulmonary veins. This form is most successful with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

Another common type of catheter ablation is cryoablation. Rather than using intense heat for ablating tissue, cryoablation uses intense cold. Other energy sources may also be used for catheter ablation, including laser energy (light waves) or ultrasound energy.

One of the newest frontiers in afib treatment has evolved from a collaboration between electrophysiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons, especially at integrated afib centers. Since both catheter ablation and the mini maze procedure have advantages, a hybrid ablation combines the best of both of them. To learn more about these hybrid procedures, see Hybrid Ablation Procedures.

Get in Rhythm. Stay in Rhythm.®

Atrial Fibrillation Patient Conference

Featuring World-Renowned Afib Experts

Get Replays

Mellanie True Hills

Founder & CEO, StopAfib.org

AV Node Ablation

One afib ablation procedure that has been done for years, but is less commonly done today, is AV node ablation. It is sometimes called AV junctional ablation or “ablate and pace.” The atrioventricular (AV) node sends electrical signals from the upper to the lower chambers of the heart. In this procedure, a permanent pacemaker is implanted to help control the heart’s electrical system. Once the pacemaker is in place, the AV node is frozen or cauterized to prevent electrical signals from being transmitted. The heart is then reliant on the pacemaker.

This procedure doesn’t stop heart palpitations. Thus, the patient may keep having afib. However, the afib signals don’t get transmitted to the rest of the heart. As a result, some patients no longer feel irregular heartbeats, but some still do.

Since the afib continues, the patient must stay on an anticoagulant medication, such as Coumadin (warfarin) or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), to prevent strokes. If atrial fibrillation continues, fibrosis (scar tissue) continues to build. Increased fibrosis is correlated with an increased risk for stroke. In addition, the heart may not work as effectively, so patients may still feel tired. This may work best in patients who already have a pacemaker or need one for other reasons.

AV node ablation is typically the atrial fibrillation treatment of last resort. It is used when other treatments have failed or in patients who are too frail for catheter ablation. Most afib patients will be offered different treatment options first before an AV node ablation is considered. To read an opinion article about AV node ablation, see AV Node Ablation: Why You Shouldn’t Have It.

Recent research suggests AV node ablation and His bundle (a group of heart muscle cells that transmit electrical impulses generated by the AV node) pacemaker implantation may be a promising option for those with afib and heart failure. In a clinical trial, 52 symptomatic afib patients with heart failure had an AV node ablation and a His bundle pacemaker implantation. Participants showed improved echocardiograms and reduced diuretic use for heart failure.1 Before permanent His bundle pacing with AV node ablation can become a standard treatment, additional clinical studies with larger populations are necessary to confirm these findings.

You Don't Have to Go It Alone

StopAfib.org was created for patients by patients to provide accurate information and genuine support for those affected by atrial fibrillation. Explore our online community and connect with other patients, families, and caregivers.

If you’re considering catheter ablation, you need to know about Catheter Ablation Success Rates and Catheter Ablation Risks. To learn more about current catheter ablation techniques and technology, see Catheter Ablation Techniques or Catheter Ablation Technology.

Catheter Ablation Related Blog Posts

Join us for a National Atrial Fibrillation Awareness Month Webinar, Hosted by Medtronic

For National Atrial Fibrillation Awareness Month, I'm excited to moderate two free afib webinars being hosted by Medtronic. The September 26 webinar features Dr. Devi Nair, Director, Cardiac Electrophysiology & Research, St. Bernards Medical Center,… Read On

Join the VIBRANT-AF Study to help improve catheter ablation effectiveness

Do you plan to have an afib catheter ablation? By joining the VIBRANT-AF Study before your catheter ablation, you can contribute your data to an effectiveness study that will improve the care of afib patients… Read On

URGENT: Please Ask Congress to Tell Medicare to Preserve Your Ability to Get an Ablation

Recently, we asked afib patients in the US to ask Medicare to preserve their ability to get a catheter ablation when needed. Unfortunately, that comment period closed in early September, but we have another opportunity… Read On

View More Catheter Ablation Posts